Welcome to Hold the Code #65, the first edition of the 2023-2024 school year!

To our incredible readers—new and old—thanks for being a part of our community. And to our Northwestern readers, we hope your quarter is off to a great start. In this edition, we explore the challenges of AI and language translation, the ethical implications of Glassdoor, and a sociological approach to innovation.

As always, if you enjoyed reading this edition of the newsletter, tell a few friends. Happy reading!

Lost in Translation

Written By: Kimberly Espinosa

Since I was in elementary school, the pressure of translating from Spanish and English and vice-versa for my parents and other family members is a memory I often come back to. This is because for the most part, I am still the one translating for my mom, and although I am no longer considered an English-language learner, there are plenty of words that I still have trouble translating when it comes to the medical field.

But I am not the only one struggling. AI, particularly in relation to language translation, is also being challenged at not just achieving accuracy level standards but also with cultural competence (e.g. honorific usage, words and that simply cannot share an equivalent translation). Language translation is important for practically any setting where a diverse range of languages are spoken. From first-hand experience and additional reading, that is especially true for hospitals, legal courts and more.

Google Translate’s Cultural Competency

You do not have to think too far to realize that AI is already a prominent tool in language learning and translation–there’s Google Translate! Simply type or speak into one side of the interface with what you want to translate, and it will output your translation. Simple, right? Or is it?

Despite my mom’s availability to use Google Translate on her phone, she does not use it, and it is not like she really can. I, myself, only feel comfortable using it because I am fluent in both English and Spanish, and it serves as a tool for support when I have to quickly translate a text.

Mini Case Study on Machine Translation

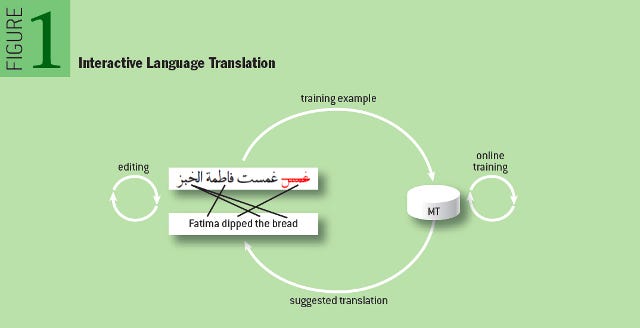

The image above, from a research Article by Spence Green, Jeffrey Heer, and Christopher D. Manning, displays an example of how a user might experience machine translation (MT). The text inputted reads “Fatima dipped the bread,” which would then be translated to Arabic–except there is a lost in translation situation. The verb (‘dipped’) which is highlighted in red from the Arabic translation includes a masculine inflection. In this specific scenario, the MT is still able to facilitate translation through speed and allows for user feedback.

For additional insight on this particular case, you can check out Natural Language Translation at the Intersection of AI and HCI: Old questions being answered with both AI and HCI.

It can seem simple to write questions like, “Why are you here today? What are your symptoms? On a scale of 1-10, how bad is your pain?” and translate them to Spanish. These might actually work given its brevity. But what about more complex sentences, or other languages in which Google might be less trained in?

Marenid Planell-Camacho, an advocate for health literacy and with an interest in bilingual health services among other related topics, discusses the shortcomings of Google Translate in health literacy. She specifically mentions cultural competence as being an important element for bridging communication between patient and physician and improving accessibility.

The truth is, although Google Translate has saved me several times from the daunting experience of not knowing English or even Spanish words in urgent situations, there is still some sort of hesitation and drawback I experience to trust Google Translate with a correct translation and even more now, with privacy.

On Google Translation & Privacy: HIPAA

By engaging in more in-class discussions and readings that touch upon data privacy, I have become more aware—or at least try to be more aware—of how technological advances are equally being checked with accessibility and privacy.

I use Google somewhat frequently: for translating long English documents to Spanish and when I see an ingredient list I want to know more about. I also use it when learning my fourth language, Korean, but only lightly because I know that it is much less accurate than when I use it for Spanish.

I have never really considered what Google is doing with what I am typing into its language translation platform until now.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requires individuals involved with administering patient health information to have policies and a protocol set that will ensure information is protected securely. This applies to information saved through physical or electronic documentation.

With Google Translate, that may be tricky. According to Systran, another machine translation platform, there is risk involved in using a public cloud service. This means personal health information becomes vulnerable from potential data breaches.

Now it makes a little more sense why I have never seen Google Translate used during my hospital visits.

“Did someone help you fill out this form?”

Next time my mom gets help with translation, it will most likely be me, or someone around (that is if there are any fluent Spanish-language speakers). I cannot help but wonder if there will ever be a time when this will no longer be true. Maybe it is already somewhere in the world! Beyond simple form filling, how will AI show up in the patient room? Will people be less, or rather, more comfortable with asking intimate, direct questions?

Let us know your thoughts in the comments below.

A Look Inside the Glass Door

Written By: Mark Fortes

As students and pre-professionals like ourselves navigate the constantly evolving landscape of the modern workplace, online platforms like Glassdoor have gained significant traction in shaping our understanding of companies. They offer a glimpse into a company's culture, work-life balance, and overall employee satisfaction. Accordingly, they receive significant traffic, with top reviews collecting thousands of impressions monthly and playing a crucial role in shaping a company’s presence and reputation. Employers realize this; Some organizations resort to costly lawsuits, often amounting to millions of dollars, in order to unveil the identities of anonymous reviewers who express dissatisfaction with their jobs.

There’s no question that online reviews are at the forefront for both companies and job seekers. Today, let’s focus on Glassdoor. It is important to first make note of Glassdoor’s policy on how employers can deal with negative reviews. From their website’s Help Center, here is their statement:

“If you believe a review violates our Community Guidelines or Terms of Use, you can flag it directly on the site and our Content team will give it a second look. If we find that we missed something the first time, we’ll take it down.”

That’s a violation

So what constitutes a violation of their Community Guidelines or Terms of Use? Here are bulleted points on their site that I found notable:

We do not allow reviews that include negative comments about identifiable individuals outside of this group [individuals in the highest positions in a company]

We don't approve reviews that include certain profanities, threats of violence, or discriminatory language targeted at an individual or group

We do not accept reviews that reveal confidential, non-public internal company information

We reject reviews that do not relate to an employer, are only a review of the product or service, or are otherwise not relevant to understanding workplace culture

But does Glassdoor stay true to its word? Tech blogger Gergely Orosz, in his article titled “Layoffs push down scores on Glassdoor: this is how companies respond,” would probably say yes. At a company with several one and two-star reviews, Orosz was able to get in contact with an HR professional who attempted to flag every one of these reviews as a violation of community guidelines, and he found that:

“Glassdoor only acted on clearly defamatory and fraudulent ones, or ones which violated guidelines”.

However, this is just one account. Orosz also describes throughout his article many “inside scoops” he was able to obtain, revealing less savory practices by some businesses.

One such practice is that employers can flag reviews where they assert an impersonator is pretending to be an employee. In such cases, Glassdoor will request the reviewer to provide evidence of their current employment and will temporarily conceal the review until this verification takes place. Naturally, some employees opt not to reveal their identity, effectively silencing the negative review. There are even websites (such as this one here) that offer negative review removal services, some with legal teams keen on finding loopholes that will allow them to successfully remove even the most legitimate reviews.

Why you should care

The use of illegitimate tactics in generating positive reviews or removing negative ones raises significant ethical concerns. Firstly, it compromises the integrity of online platforms like Glassdoor, undermining their purpose of providing genuine insights to job seekers. When reviews are artificially inflated or biased, individuals searching for employment may make ill-informed decisions, leading to potential mismatches in company fit and employee satisfaction.

Moreover, manipulating online reviews undermines the trust between employers and employees. By stifling genuine feedback, organizations hinder their own opportunities for improvement and growth. Employees should feel comfortable expressing their concerns and experiences without fear of retribution, enabling companies to identify and address issues constructively.

Maintaining transparency and authenticity in managing online reviews is crucial to uphold the integrity of platforms like Glassdoor. Employers should foster an environment that encourages open feedback from employees, without the use of coercion or incentives. This ensures that reviews reflect genuine experiences, providing valuable insights to job seekers.

While Glassdoor generally upholds its community guidelines and standards, it is important to recognize that Glassdoor is free for job seekers/employees. In reality, Glassdoor’s customers are the companies and their recruiters! Their money is made through job postings, advertisements of these postings, and employers’ branding. All in all, it is crucial for users to approach Glassdoor reviews with a grain of salt, considering multiple sources of information and conducting thorough research before forming an opinion about a company.

What’s behind innovation?

Written By: Ian Lei

From remarkable strides in AI to advancements in medicine that are reshaping our world, we are situated in an exciting age of innovation. When we think of the companies leading the charge, it's natural to connect them with notable individuals like Steve Jobs at Apple, Sam Altman with OpenAI, and Elon Musk at Tesla. However, it's easy to fall into the misconception that innovation solely springs from individual or corporate efforts, overlooking the significant role that broader institutional contexts play in shaping it.

It was a mindset I held until I came across an article out on display at the Pritzker School of Law last quarter written by Professor Laura Pedraza-Fariña. Titled “Patent Law and the Sociology of Innovation,” the article calls attention to the importance of patent law in influencing innovation and the need to analyze the underlying social factors that affect it.

“Science sometimes sees itself as impersonal as ‘pure thought’ independent of its historical and human origins…But science is a human enterprise through and through, an organic, human, growth, with sudden spurts and arrests, and strange deviations.” – Oliver Sacks, a British historian of science.

Factors that influence innovation

In Part II of her article, Professor Pedraza-Fariña explores three types of social phenomena that influence the speed and nature of innovation: specialization, relationships of trust and authority, and unexpected discoveries. She writes that innovation does not rely only on current scientific ideas, “or on the totality of available knowledge.” Instead, “innovation is discontinuous and nonlinear.”

1. Specialization

Looking at innovation through the lens of communities of practice, rather than individual researchers, helps us grasp how innovation, especially breakthroughs, occurs at the crossroads of various social networks. For example, when scientists shift between communities, they bring along their skills and ideas, applying them to new fields. This often leads to innovation when tools from one discipline are used in another, when problems are redefined with a fresh perspective, or when results are given new interpretations.

For example, the migration of a group of physicists to biology resulted in the discovery of DNA as the genetic material, which, in turn, sparked the birth of molecular biology.

Circumstances that inhibit intellectual migration and interaction between communities (coined “innovative delay”) include cognitive impairments and structural impairments.

Cognitive impairments: The nature of specialization itself can prohibit scientists unfamiliar with the techniques or the body of knowledge of another discipline from evaluating that field’s scientific discourse. Furthermore, specialists in a particular field may not be aware of certain findings or technological advancements and their potential impacts because they tend to focus on a narrow range of related specialties.

Structural impairments: Vested interests within a specialty can impede intellectual migration in two ways. Firstly, they impose personal costs on those switching disciplines, including social isolation and a decrease in social status. Secondly, they encourage resistance to outsider perspectives within the discipline. Vested interests can shape research agendas by determining what is considered "interesting" or "valid" in research projects.

2. Trust and Authority

Relying on trust and authority can help in evaluating research proposals and experimental outcomes, but it can also hinder innovation. For instance, scientists may hesitate to challenge authority figures, and some scientific communities may be skeptical of "outsiders" with valid experimental data.

3. Unexpected Discoveries

An examination of historical instances of unforeseen breakthroughs in scientific progress reveals three distinct contexts. These scenarios involve such breakthroughs occurring either by:

Sheer coincidence

Charles Goodyear’s discovery of vulcanized rubber

Unforeseen byproducts unrelated to the primary research focus

In 1972, scientists working at Sanofi, a pharmaceutical company, stumbled upon products that had anticoagulant properties when they were actually trying to find substances that could boost anti-inflammatory effects.

Unconventional observations directly tied to the research inquiry at hand.

These accidental discoveries are likely to be discovered by independent researchers at the same time and to be actively investigated by them. For example, the discovery of reverse transcription in 1970 – that enzymes could make DNA from RNA – occurred simultaneously at laboratories of two different scientists: David Baltimore and Howard Temin.

Why does this all matter?

Professor Pedraza-Fariña provides compelling reasons for a sociological approach to innovation, primarily within the context of patent law. This perspective allows patent law to align more closely with the actual dynamics of innovation. Moreover, it offers a valuable framework for addressing questions pertaining to the Supreme Court's role in determining patentability.

Outside the context of patent law, I wanted to outline some other reasons for the importance of a social perspective:

Inclusive Innovation: Recognizing social factors enables an inclusive approach to innovation. This ensures that innovation benefits a broader range of people and communities, which ultimately unlocks new opportunities and untapped potential for innovation.

Policy Formulation: Policymakers can use insights into social factors to design laws not just around patentability that promote innovation.

Collaborative Efforts: Recognizing the collaborative nature of innovation, including the social aspects, can encourage partnerships and collaborations across sectors and disciplines, fostering a more vibrant innovation ecosystem.

My final thoughts

Professor Pedraza-Fariña's article left me with a profound insight into the interplay among scientific communities that contribute to innovation. It also made me reflect on the communities located here on campus. As I’m entering my junior year, I’ve been thinking a lot more about my time so far at Northwestern and how to make use of the latter half of my college experience.

I’ve been most fortunate to take courses in a variety of disciplines, including Journalism, Economics, Art History, Design, and Philosophy, that have provided me with different lenses to view the world through. Additionally, I’ve also learned so much from conversations with my peers who have varying backgrounds and interests. While I’m not participating in groundbreaking scientific research, tapping into different communities on campus has sparked my personal evolution – a form of “innovation” in itself.

Additional Reading: